India’s Labour Advantage is Slipping

Why are real wages now set to rise in India?

Back in June 2024, Larsen & Toubro (L&T) revealed it was facing a severe shortage of over 45,000 workers across its operations, including 25,000–30,000 labourers in its construction division. Multiple factors were at play, including extreme weather (rains), disruptions due to elections, and other logistical challenges.

In May 2025, D-Mart reported a consistent decline in margins, with its EBITDA margin dropping to a three-year low of 7.9% in FY25, compared to 8.3% in FY24 and 8.7% in FY23. One of the primary reasons? Wage pressure.

“Surge in wages of entry level positions due to demand/supply mismatch of skilled workforce”

- Mr Neville Noronha, CEO & MD, Dmart (May 2025)

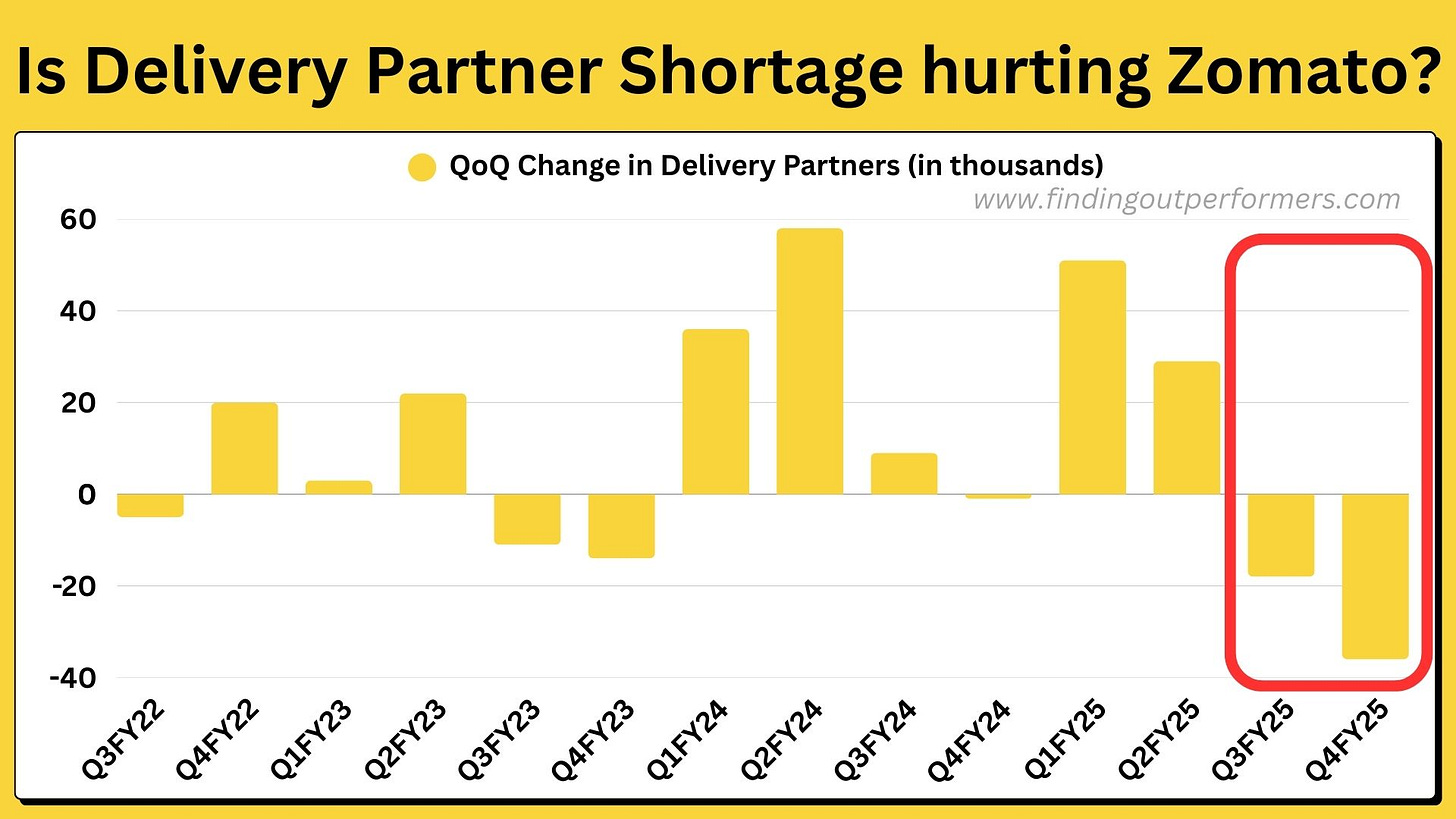

In another instance, India’s largest food delivery giant, Zomato, revealed in its Q4 FY25 results that it had lost around 54,000 delivery partners over the past six months. This shortage appears to be putting pressure on the existing fleet, leading to longer delivery times. The company went ahead and shut down recent initiatives like Zomato Quick and Everyday, which could be straining its already shrinking delivery fleet, as these services potentially require a higher number of partner availability to fulfill 10–20 minute delivery commitments.

“We anyways see a slight supply crunch on the delivery partner side in summers. This time, that got compounded in some ways because of rapid quick commerce expansion across the board”

- Akshant Goyal, CFO, Zomato, (May 2025)

In today’s blog, we deep-dive into whether urban India is on the brink of a structural labour shortage — and whether this shift could begin to weigh on India Inc’s margins as real wages start rising again. Now let’s get started!

Domestic Migration is reversing!

People migrate from rural to urban areas mainly in search of job opportunities, higher wages, and better living conditions. Low agricultural income, underemployment, and limited access to services in rural areas often push individuals toward cities in hopes of a better life. But what if that lifestyle improves without even migrating?

While India’s population has grown from about 1.2 billion in 2011 to over 1.4 billion today, the number of migrants during this period has actually declined!

“Since Census 2011, the number of migrants has reduced by about 11.78%, to ~40 Crore and the migration rate has also reduced to 28.88%.”

- Economic Advisory Council to PM (Dec ‘24 Paper)

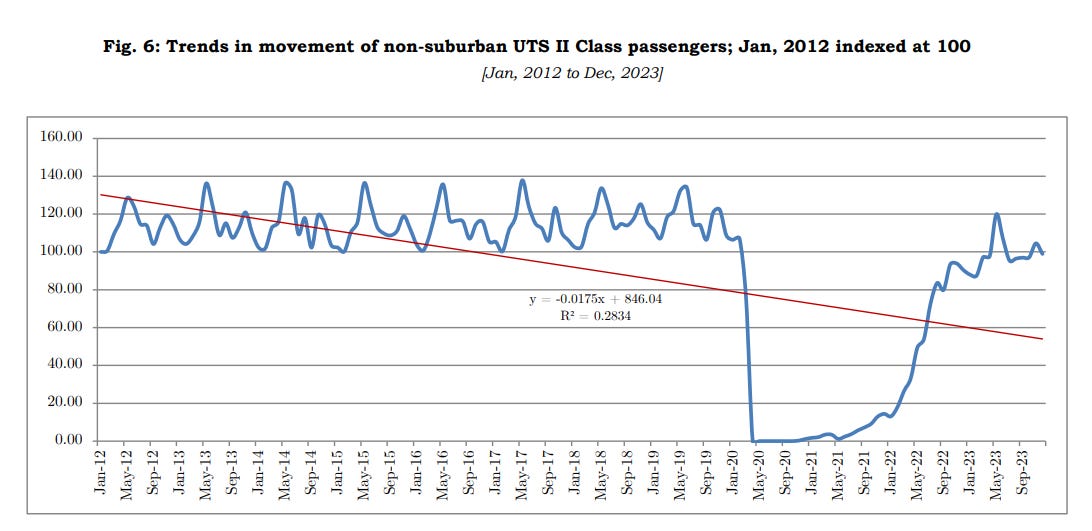

Let’s take a look at the month-on-month changes in the total number of non-suburban train passengers from January 2012 to December 2023 - a reasonable proxy for tracking on-the-ground movement and potential migration trends. (Source)

The level of mobility seen before COVID-19 hasn’t fully returned, even few years after the pandemic. Something has shifted. Some attribute this change to the ongoing free foodgrains scheme, which benefits over 800 million people, or to the growing number of income transfer schemes for women being rolled out by various states — including Karnataka, Odisha, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Delhi and Tamil Nadu. In total, 14 states either have such schemes in place or are preparing to launch them.

The graph below from Axis Capital shows that nearly 0.6% of India’s GDP is now being spent on direct income transfers - a mechanism that was virtually non-existent before COVID-19. It’s striking that a country still struggling with basic public infrastructure has shifted so quickly toward cash-based welfare. When such incentives are in place why would someone even migrate?

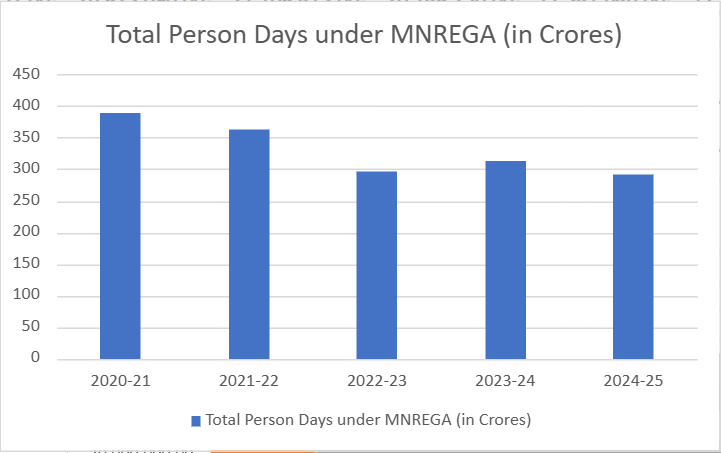

Falling demand for MNREGA

MNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act), launched in 2006, is India’s largest rural employment guarantee scheme, assuring at least 100 days of wage employment annually to rural households willing to do unskilled manual work. It is fundamentally a demand-driven scheme - any rural household can request work, and the government is legally obligated to provide it within 15 days, failing which the applicant is entitled to an unemployment allowance. While in practice the scheme faces supply-side constraints, such as budget limitations, it still serves as a useful indicator of distress in the rural economy. High demand for MNREGA work typically signals a shortage of alternative employment options, which often pushes more people to migrate to cities in search of better-paying jobs.

The demand for work under MNREGA has been been falling after making a peak during Covid. In fact, for April 2025, households demanding work under MNREGA decreased further by 6.6% compared to April 2024. This figure is also the lowest for April month since 2020-21, therefore indicative of trend that there is overall a falling need for employment in rural India, which further indicates that the need to migrate for cities is also reducing.

Large Population, Larger Profitability?

India enjoys a labour advantage, and its expanding upper and middle class is increasingly reliant on blue-collar and gig workers to sustain urban lifestyles. From essential services like cooking, cleaning, and driving to newer conveniences such as doorstep grooming, instant grocery delivery, and home repairs, a wave of unicorn startups has emerged by catering to this vast segment - powered by a growing army of low-wage workers.

McKinsey forecasts that by 2030, India’s 70% of the 90 million new anticipated jobs in current decade will fall under the category of blue-collar roles.

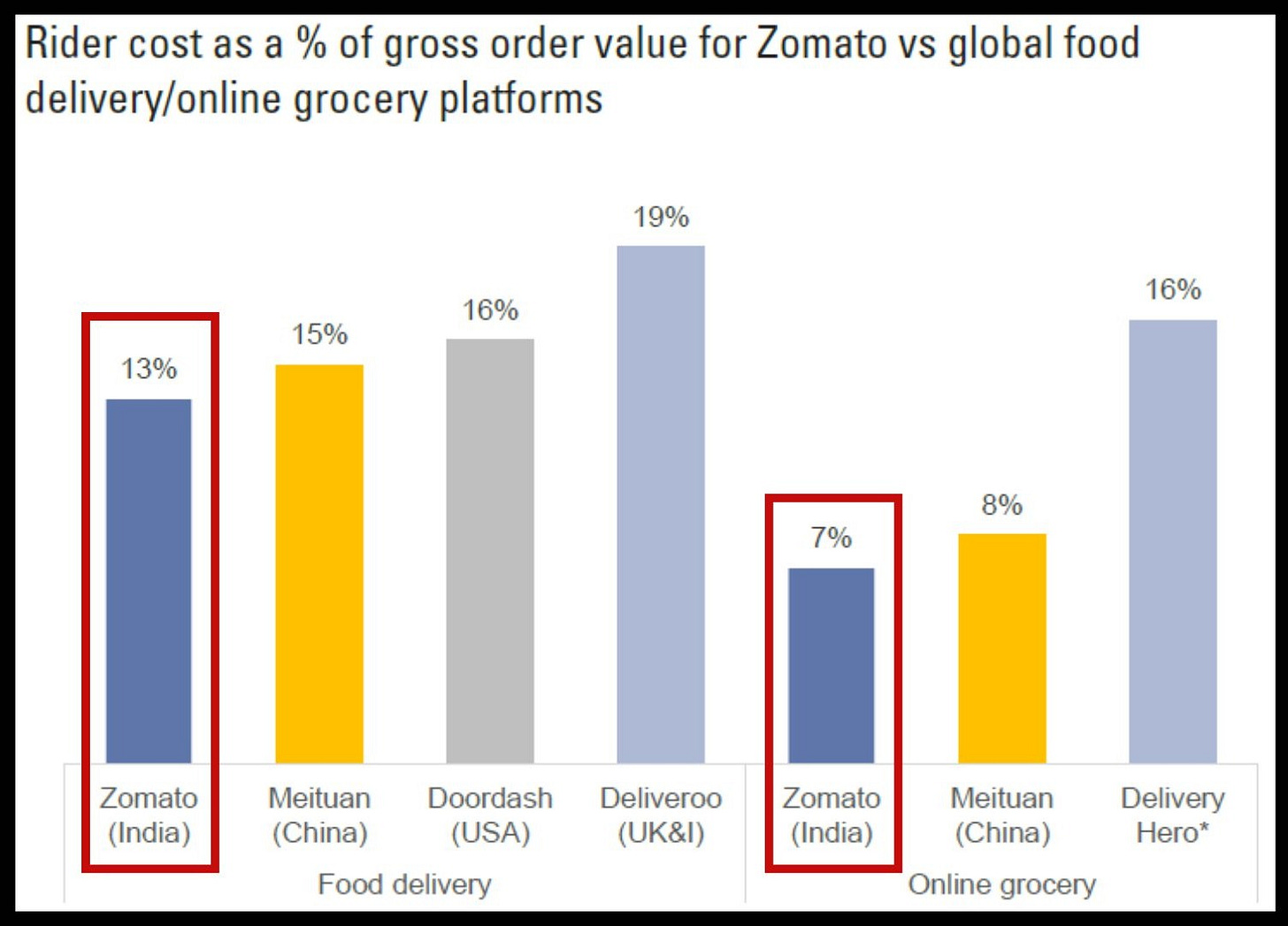

So far, income inequality in India has also driven many startups to build businesses around a large labour base, aiming for long-term margin expansion. On the revenue side, they target the top 20% of income households - customers with high average order values who are increasingly reliant on platforms offering services like food delivery and quick commerce. On the cost side, a vast working population aged 20 to 40, with limited job opportunities, has helped keep wages suppressed for years, enabling startups to scale without significant labour cost inflation.

As shown in the chart below from Goldman Sachs’ 2024 report, companies like Zomato in India hold an advantage over its global peers primarily due to significantly lower labour costs here.

But what happens if this advantage begins to erode, as real wages for the blue-collar workforce start rising sustainably? Let’s explore that next.

The Apple of our Eye: Stagnant Real Wages

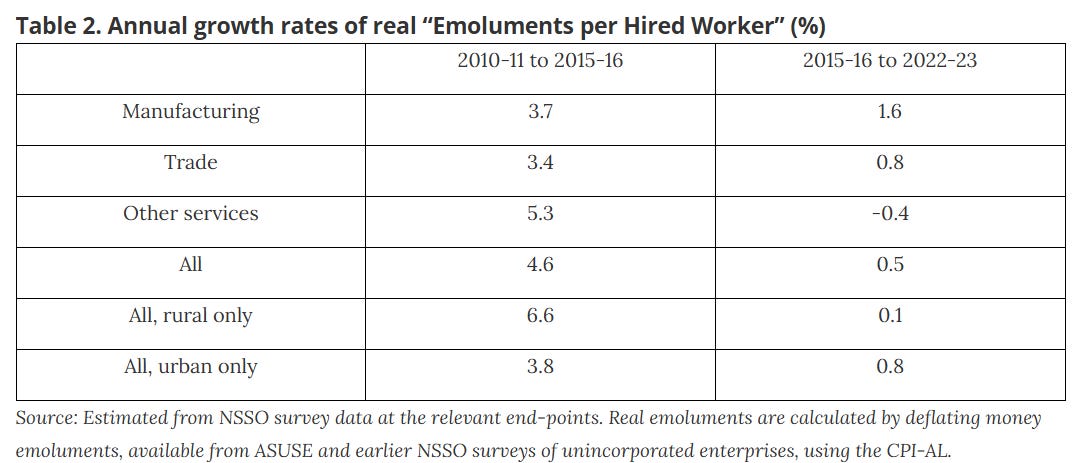

Real wages in India have remained virtually stagnant for several years, even as GDP has continued to rise - an indication that economic growth is not translating into improved living standards for workers. Data from the Labour Bureau’s ‘Wage Rates in Rural India’ series and the NSSO show that wages for general agricultural, non-agricultural, and construction workers have seen little to no real growth since 2015, underscoring a deep structural issue in India’s labour market. Whether in manufacturing, trade, or across rural and urban divides, real wage growth has been minimal across sectors. (Source)

While the poverty continued to fall during this period of 2015 to 2023, the reason why there is hardly any real wage growth is also the steadily rising working-age population (having significant increase in entry level age employment seekers of 15-25 years) in the total working population has been rising steadily in the last 20 years. While poverty reduced, real wages got stagnant.

But the similar statistic also suggest that this ‘demographic dividend’ here is about to come to an end as our median age has now crossed 28 years median age mark.

Adding to it, while India’s share of ‘Agriculture sector’ has been constantly decreasing for years now, but the share of workforce engaged in agriculture has been steadily increasing! While one might have expected the share of the workforce engaged in agriculture to decline after the COVID-related spike, the opposite has occurred - in 2022, 2023, and 2024, a growing percentage of India’s workforce has become increasingly dependent on agriculture, especially female workforce.

About 46.1% of the workforce engaged in agriculture in 2023-24, up from 42.5% in 2017-18.

This brings us back to our earlier point: with income transfers and free foodgrain schemes in place, the incentive for the rural workforce to migrate to cities and seek employment in other sectors has diminished.

So Are Real Wages Set To Rise?

At the end of the day, it boils down to the demand-supply mismatch, which decides the growth in real wages. The higher the demand compared to supply in urban India, the higher the rise in wages. While real wages have remained stagnant for the blue-collar workforce across sectors over the past decade, things on the ground are changing rapidly, with early signs of shortages emerging and becoming more pronounced in urban India as the migration from rural is significantly reducing. If this marks the onset of a structural trend, it will begin to reflect in the future margins of labour-intensive sectors/companies, including textiles, tourism and hospitality, logistics, warehousing, and last-mile delivery companies. We shall continue to track it closely in our future blogs.

We hope you enjoyed reading our analysis. Connect with us on LinkedIn here: Aditya Grover and Kinjal Karwa

Finding Outperformers is a free-to-access website, and each blog takes a month of effort to finalize. If you've read this far and you find our research useful, consider supporting our efforts by contributing here:

Read more our latest blows below⬇️

Disclaimers-

We are not a SEBI registered advisors; personal investment/interest in shares can exists for any company mentioned above; this isn’t investment advice but our personal thought process; DYOR (do your own research) is recommended; Investing & trading are subject to market risk; the decision maker is responsible for any outcome.

I would say slowly and gradually there is a shift in the mindset of a laborer. If he migrates to tier-1, metro city and the conditions are same what he/she used to get in village setup [with no growth in real wages]; then why to shift altogether. I have experienced this 1st hand in many villages in RJ & GJ, so can say this with confidence.

Practical Situation: Avg laborer in India is having a marginal land for farming.

a) Past Scenario: He bought inputs -> did sowing -> reaped the yield -> sold it in Mandi [Avg cycle was 4-5 months, and during this cycle he didn't had money - this was more of a gamble farmer played but didn't had clarity on the final output due to rains, weather, pests and other factors].

b) Present Scenario: He buys inputs on finance [avg ROI 8% to 24%] -> does sowing -> reaps the yield [Village/FPO/SHG level-funded farm mechanization to some extent] -> either market linkage startup buys the output at good rates or he goes to Mandi and uses his option of MSP -> pays back the financier [MFI/FPO/Startup/NBFC at agreed ROI] -> gets the better credit line for future farming.

Believe me this is happening. Thanks to Govt.

One of the reasons is massive handouts as currently identified. The consequence of such can be far reaching which is not discussed here (could be a seperate topic)